The condition of forests is deteriorating, they are getting sick and dying. This issue concerns not only scientists and forest owners but also the public. The condition of forests is deteriorating, they are getting sick and dying, and this is a concern not only for scientists and forest owners, but also for the public. Against the backdrop of climate change and anthropogenic pressure, the susceptibility of trees to damage by insects and pathogens is increasing, and pests and pathogens themselves are spreading to new territories, changing seasonal development cycles and increasing their harmfulness. It is not without reason that the activities of Section 7 “State of Forests (Forest Health)” of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations (IUFRO) and the 23rd session of the congress of this organization, which took place on September 19-22, 2017 in Freiburg (Germany) to commemorate the 125th anniversary of its founding, are devoted to issues related to forest diseases (LV, 2017, No. 9-10). Separate working groups consider root and root rot (7.02.01), diseases of leaves, shoots and trunks (7.02.02), vascular diseases (7.02.03), diseases caused by viruses and phytoplasmas (7.02.04), rust of forest species (7.02.05), interaction of diseases and the environment in the drying of forests (7.02.06). The activities of working group 7.02.09 are devoted to late blight of forest species (Phytophthora), group 7.02.10 - pine wilt caused by the pine stem nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Attention is increasing to previously little-known diseases: downy, downy and dwarf birch in Finland and Germany are affected by the CLRV virus (cherry leaf-roll virus), and mountain ash by the EMARaV virus. To cure a disease, the cause must be identified. A sick person can tell where it hurts. A sick tree is silent. In the case of damage by insects, rodents or ungulates, it is often possible to identify the “culprit” (either you saw who bit, or certain signs indicating it are left – excrement, molted skins, wool). In the case of a tree being affected by a disease, the cause is not always obvious. A tree’s disease is its reaction to constant “irritation” by an infectious organism – a pathogen. The disease manifests itself in certain symptoms (color changes, the presence of wounds, necrosis and ulcers on certain parts of the plants, their deformation or drying out) or signs (the presence of fruiting bodies, spores, mycelium), which reduce the intensity of growth, fruiting, quality of wood, fruits or seeds. A true disease is caused by living organisms that reproduce in the plant or reside in it during a certain part of its life cycle. A person is also a living organism, but he does not reproduce in the plant and does not reside in it during a certain part of his life cycle. A person damages trees directly mechanically (when pruning branches or cutting down neighboring trees), chemically (by applying arboricides or fertilizers) or indirectly due to pollution of air, soil or water bodies with industrial, agricultural and household waste. Therefore, like abiotic factors (wind, fire, drought), anthropogenic factors cause non-communicable diseases, which in foreign literature are called disturbances. The disease can occur only in the presence of a pathogen (a disease-causing organism - fungus, bacteria, etc.), which encounters a susceptible host (plant) under favorable conditions for the development of the disease. Ideally, protection against diseases ensures the exclusion of all three conditions: preventing the spread of the pathogen and growing resistant tree species and forms in conditions most favorable for the growth of plantations.

Forests Are Dying... How to Help Them Survive?

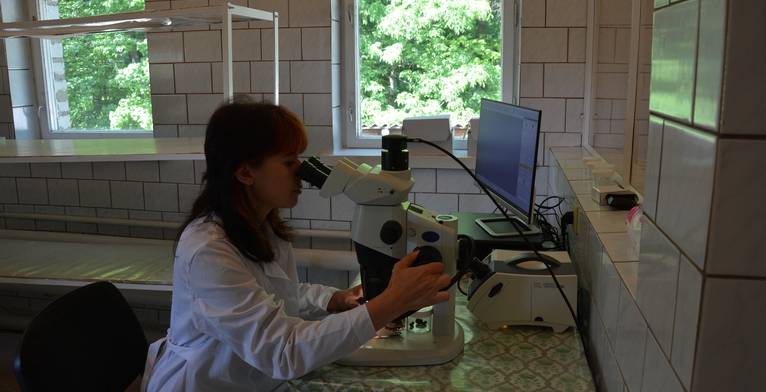

To prevent the spread of a pathogen, it is necessary to know its development cycle and the development cycle of the disease well. A typical disease cycle includes the following components: the formation of an infectious inoculum (spores, hyphae, bacterial cells, virus particles, nematodes, etc.), its spread, penetration into the plant, spread in its tissues, secondary cycles and production of a new inoculum, survival in the winter. The inoculum can be on seeds, plant residues, weeds, in the soil, spread by wind, splashes of water during irrigation or rain, fall from the surface of tools during pruning or care. It can be carried by insects that feed on a diseased plant. So, to prevent the spread of forest diseases, the development cycle of pathogens under certain conditions should be studied by mycologists or bacteriologists, and the routes of transmission - together with entomologists. Since the risk of disease development on a resistant plant is minimal, selection for resistance should take the leading place in protecting plants, and especially forests, from diseases. Under favorable conditions for the pathogen, it develops in a weakened plant. Thus, growing a light-loving plant in the shade increases its susceptibility to infection. On the other hand, high-intensity pruning and a sudden increase in lighting cause a strong weakening of trees, increase the risk of sunburn and frostbite, which are barriers to infection. Mixed stands with the correct selection of species use soil conditions more effectively and are resistant to many factors, including harmful insects and pathogens. Therefore, growing mixed stands taking into account the requirements of the species and timely care of moderate intensity largely prevents the spread of diseases. Researchers from universities and research institutions in different countries, within the framework of International Projects, comprehensively study the biology and harmfulness of pathogens of Dutch elm disease (Ophiostoma novo-ulmi), chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), plane tree wilt (Ceratocystis platani), pine dothistroma (Dothistroma septosporum (Mycosphaerella pini) and D. pini), ash blight (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus), and develop measures to prevent the spread and development of these and other diseases. Each project involves mycologists (who study pathogens), phytopathologists (who study the spread and development of the disease in a certain plant group, assess plant resistance, and develop protective measures), breeders (who try to select or breed resistant forms or varieties of plants) and foresters (who must make adjustments to forestry activities aimed at reducing the vulnerability of plantations to the disease). It is precisely this comprehensive approach and temporary teams of independent scientists that yield fruitful results. Some projects (in particular, regarding pine dotystromosis and ash chalaro necrosis) also involved executors from Ukraine. At the same time, several scientists involved in projects that finance only trips to conferences and internships cannot, without the support of official bodies and enterprises of the forestry sector, examine 10 million hectares of forest plantations and identify dangerous pathogens. Unfortunately, forest phytopathology in Ukraine has not reached a high level of development, which is largely due to the high requirements for equipment, reagents and research conditions. In fact, we do not know not only about the presence of new diseases in the forests of Ukraine, but also about the spread of such diseases that are known from textbooks! There are no official connections between forestry institutions with classical mycologists of universities, the Institute of Botany named after M. G. Kholodny, the D. Zabolotny Institute of Microbiology and Virology, which are armed with knowledge and equipment. If a disease spreads in the forest, this gives grounds to appoint a sanitary felling. A lot is written about increasing the resilience of the forest, but in fact such measures are not included in the technological maps, and funds are not allocated for them. The allocation of “pines in root sponge foci” to a separate economic section makes it possible to appoint a main use felling earlier. (Employees of the Ukrderzhlisproekt LLC stubbornly write “foci”, although they have repeatedly explained that a “foci” is a controlled fire, and a “foci” is a place from which something spreads – in particular, an infection). At the same time, it is difficult to say by what signs such plantations were singled out, without having a laboratory base for determining the causative agent of this disease. After all, in many regions this fungus does not form fruiting bodies. More than 20 years ago, a mycologist, now a professor at Kyiv University, M. M. Sukhomlin visited many forestry enterprises, where the root sponge foci were listed on the papers, and did not find any signs of the pathogen fungus. On the other hand, the drying of pine trees in the root sponge foci has recently sometimes been “attributed” to bark beetles. Advanced specialists make arrangements through personal contacts, participate in competitions and receive grants for internships and sample analysis at foreign scientific institutions, since the conclusion about the presence of a particular pathogen must be confirmed by molecular methods by comparing the obtained indicators with the database. The situation is somewhat better in agriculture, where certain costs are borne by international companies that produce fungicides or introduce advanced technologies into crop production. In forestry, there is a specific view of tree diseases. If trees in a greenhouse or nursery get sick and die, they try to protect them with fungicides, the list of which has not been updated for decades. This is due to the fact that only in Ukraine do pesticides for agriculture and forestry are registered separately. The company has to pay a considerable amount for the registration of the drug. The cost of the drugs that the agriculture sector will purchase will cover this amount, and the forestry sector believes that it is better to cut down trees and resow the seeds than to spend unnecessary money. And then they blame science for not inventing a free means of protecting the forest. Since we do not know what diseases the forest should be protected from, and what drugs to use to protect it, it seems that dangerous diseases do not exist at all. In practical classes on phytopathology, students from dozens of forestry faculties look at drawings and diagrams of the development of pathogenic fungi or bacteria. Sometimes they are shown fruiting bodies of tinder fungus, moldy acorns and other seeds. Teachers do not have the opportunity to show how to grow pure cultures of pathogens, how to identify them, store them, and even more so how to prepare samples for accurate determination using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). So how can graduates of forestry faculties, when they come to production, be able to recognize this or that disease “by eye”. It has long been proven that in protection against diseases, fungicides are a temporary measure. Fungi quickly become resistant to them. Much longer resistance can be ensured through selection. At the same time, the selection of forest species is aimed at productivity, motivating it by the fact that a tree, if it has reached a certain age and accumulated a large mass, is already resistant. But such a tree could simply not come into contact with pathogens and grow in favorable environmental conditions, and this does not mean that its offspring on an unfavorable background will also turn out to be “tall and slender”. In many countries, numerous experimental nurseries and plantations have been created, in which forms of forest species are selected that are resistant to a particular disease or to their complex, and tests are carried out on a suboptimal background, and sometimes even artificially infect plants. Quite a lot of money is currently allocated for the development of biotechnology of forest species, and material for propagation is selected from plants with the best growth indicators without taking into account resistance to diseases. If only the forest industry had allocated at least part of those funds for the creation of phytopathological and mycological laboratories at forest protection enterprises and in industry research institutions!!! Employees in such laboratories should be graduates of specialized departments of biological faculties of universities who are qualified to carry out such work, able to apply for a grant for an internship in a relevant foreign institution, if necessary, until we fully provide ourselves with equipment, reagents and appropriate conditions for work. Valentina Meshkova